Roller coaster resonance: Translating speed to pulse

by Luke Nickel and Caitlin Rowley

In his piece for Zubin Kanga and the Cyborg Soloists project, hhiiddeenn vvoorrttiicceess, Luke Nickel tackled a challenge which had been in his mind for some time but had been beyond his technical capabilities: how to use the speed of simulated roller coasters as tempo in a piece for live performance.

Zubin Kanga performing hhiiddeenn vvoorrttiicceess at Submerge Festival, Manchester, 2022. Photograph by Brian Slater.

Nickel has been passionate about roller coasters since he was a child, and hhiiddeenn vvoorrttiicceess is one of a series of roller-coaster-inspired works that he has been making since 2018. But hhiiddeenn vvoorrttiicceess is the first piece where he has been able to directly use the telemetry data of the simulated roller coasters he designs to shape the material and performance of a piece of music.

It was important to him not to ‘map' roller coaster data onto specific musical values—he didn’t want to make a piece that claimed to somehow represent a roller coaster. Nickel prefers the idea of ‘translating’ data outlined by James Saunders in his article ‘no mapping’ (2016). “Translating highlights the source,” writes Saunders, “it does not obscure it. The substance of the original material is at least partially retained in the new context. We do not need to be told what we are hearing and what it represents. It is self-evident [… Translating] embodies the world rather than represents it.” Further to this idea, Nickel proposes the idea of ‘resonance’ between the two concepts: a reflexive relationship between music and simulated roller coasters where parameters and characteristics of each field affects the other.

Nickel uses the roller coaster simulator game No Limits 2 (an updated version of the same software he used when he was a child) to design the roller coasters used in his work, and often the structures he builds would be impossible to create in the physical world. No Limits 2 has a telemetry interface which allows other programmes to read data generated by the simulated roller coasters, such as speed, forces and orientation. This feature is intended to allow things like motion platforms to be connected to the simulator, bringing a physical dimension to the simulated ride experience. What Nickel wanted to do, though, was to translate this data into a tempo curve which could precisely mirror the changing speed of an onscreen ride.

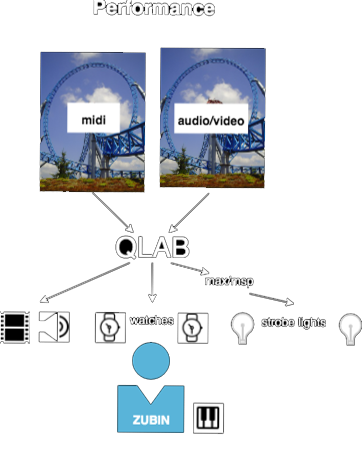

He worked with Soundbrenner to get the translation happening: from the telemetry data from No Limits 2, to a pulse from a Soundbrenner Core device on the pianist’s wrist (or, as it turned out, a Core on each wrist, each tapping the tempo curve of a different roller coaster and several Cores pulsing directly against the strings of the piano). Soundbrenner’s developer wrote a Python script to retrieve the telemetry data and send it into a Max/MSP patch, which converted it into MIDI that could be read by their iOS app to control the Core in real time.

Once this was working, the the structures and materials of the piece had to be developed, and finally it had to be made stable for performance. During development, everything was being processed in real time, but for performance, finding a simpler, reliable system could reduce set-up time for this complex piece and make identification and resolution of any problems much easier. Nickel’s solution was to export fixed files for video/audio and related MIDI files:

Qlab cueing software can start these files simultaneously, ensuring perfect synchronisation. The MIDI file that feeds the tempo data to the Cores is also fed into a Max/MSP patch to create the strobe light flashes used in the final section of the piece, tying their visual rhythm to the speed of Nickel’s impossible roller coasters.

Our video of Zubin Kanga performing hhiiddeenn vvoorrttiicceess at Submerge Festival in Manchester is out now. View it here →

References

Saunders, James. 2016. “no mapping”, MusikTexte 149, May 2016: ‘The New Discipline’. English version. <https://musiktexte.de/WebRoot/Store22/Shops/dc91cfee-4fdc-41fe-82da-0c2b88528c1e/MediaGallery/Saunders.pdf> accessed 6 September 2022.